"Dispelling the Myth of the New Lesbian Jesus" or "Why Hayley Kiyoko is Terrible"

I am going to preface what will probably be an unpopular critique of Hayley Kiyoko by admitting that I do get excited over any shred of queer visibility in popular culture. I am not a monster. Admittedly, I have traversed the Kiyoko Youtube wormhole and surfaced hours later, hungry, thirsty and exhausted. I get it, I do. But she’s still terrible. And she’s no lesbian messiah.

The Queen.

I can’t begin to imagine how differently my formative years would have played out had there been an unapologetically gay pop star on my radar. I’ve always had Madonna—she was easy to queer. Sometimes she performed it convincingly but mostly she just played the part and I knew it. It was, however, better than nothing. At 16, I scoured books and music magazines and became a kind of gay investigative journalist, searching for signs of lesbianism in interviews and album lyrics. And when the well came up dry, as it often did, I became adept at the art of projection. I projected all of my lesbian hopes, dreams and aspirations onto Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville. I projected them onto Shirley Manson in Garbage’s “Queer” video. I projected it over and over again onto the kiss between Nina and Louise in Veruca Salt’s “Seether” video—which I had, of course, recorded on VHS tape. When Patty Schemel the drummer of Hole came out in Rolling Stone Magazine, I celebrated, privately, over a Kahlua and milk in my bedroom. I was not alone in my sexuality—or my alcoholism, as it turns out—but that’s another story.

I hate this.

An aging lesbian, I enthusiastically celebrate public acceptance of any and all things GAY—of women like Hayley Kiyoko who insert themselves into spaces historically reserved for cis men, like that leopard print stool on the Expectations album cover. I do not, however, celebrate the cooptation of the male-gaze and would prefer burning that script to flipping it. If a young, successful, queer, female entertainer is celebrated for embodying Justin Bieber-esque ‘swagger’—pouting under stage lights, licking her lips while looking women in the audience up and down—it’s probably time to reevaluate our definition of ‘progressive,’ ‘feminist,’ artists. I look forward to the day when a queer woman can be a successful entertainer without objectifying other women. I’ll have a party.

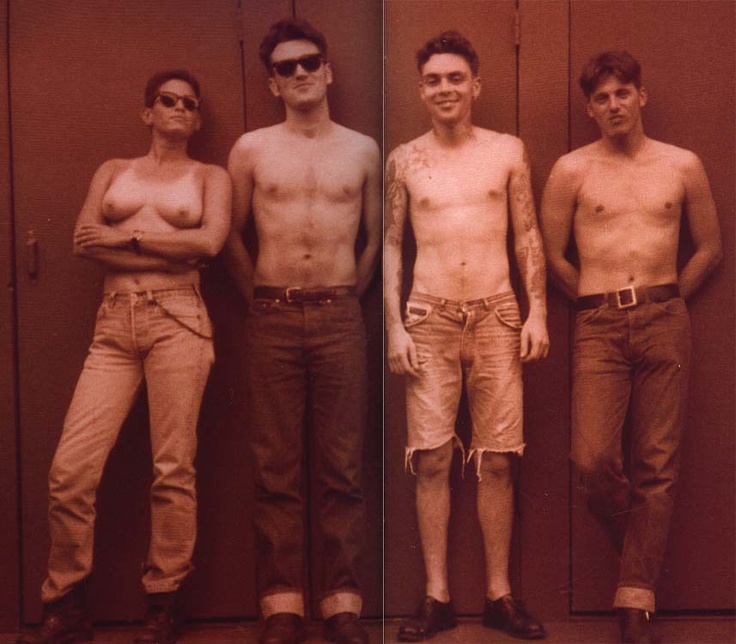

Phranc and The Smiths in 1992

The history of rock and pop music is actually very queer when you scrape away the impenetrable layer of heterosexual cis men at the top. Expressions of same sex desire and gender fluidity existed before there was language to describe it. In 1936, Lucille Bogan recorded my favorite song of all-time, BD Woman’s Blues, a coded ode to “bull daggers” or bull dykes: “B.D. Women, You sure can’t understand/ They got a head like a sweet angel and they walk just like a natural man.” And recent Rock n’ Roll Hall of fame inductee, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, was openly bisexual, an interpretation often buried in rock history and scholarship in favor of placing focus on legacy and musicianship. In the 80s and 90s, there were openly gay mainstream rock and folk stars like Melissa Etheridge, K.D. Lang, the Indigo Girls, while the Queercore movement manifested, congruently, as an anarchic response to homophobic mainstream culture—similar to how Olivia Records was born in 1973 as a reaction to overt sexism in the music industry. And our patron saint, Joan Jett, was a visibly, albeit silent, lesbian with an attitude well before Hayley Kiyoko rebranded an entire year #20GayTeen. Most openly gay progenitors did not achieve mainstream visibility—and the ones who did were the ones who were able to be commodified, sold, and consumed. Butch and former punk turned All-American-Jewish-Lesbian-Folksinger, Phranc, had a major label deal in the 80s but it’s a lot harder to sell a visible butch lesbian singing songs about politics and being gay (during the Reagan/ Bush years) than it is to sell commercial pop music written by a former Disney star.

Spice Girls

Hayley Kiyoko is to queer culture what the Spice Girls were to Riot Grrrl: An inoffensive, commercially viable version of a countercultural movement.

Bikini Kill

There are pros and cons to this commodification, of course—it’s not all bad. The downside of this commercialized “queer revolution” is that it is being heralded by the most physically palatable version of queerness—the same way The Spice Girls were the more conventionally attractive, virtually harmless version of those hairy feminists in Bikini Kill— in an era of gross capitalist consumption. And isn’t that the antithesis of queer culture? To participate in your own commodification and call it visibility? The upside is that Kiyoko is a femme, and she is aggressively gay. An aggressively gay femme. What a beautiful phrase! She even corrects people who mislabel her. She fights the good fight (femme invisibility) and illuminates the daily struggle of gay women who lack the physical (often masculine markers, septum rings and/or an undercuts) distinctions needed to be taken seriously, or recognized at all, within the LGBTQIA community. She’s a visible, aggressively gay pop star with a diverse, global fan base. And the vehicle for her women-loving-women message is radio friendly pop which means she won’t be exiled to the Land of Lesbian Music and her message and same sex video makeouts will be consumed by a wide audience. Sure, she’s making someone a lot of money but she has the ability to change how queer people are perceived on a grand scale.

So, my problem is not that Hayley Kiyoko exists. My problem is that her music is terrible (objectively); she’s not the first lesbian anything and if you work in music media and perpetuate that myth, you are complicit in the silencing of queer women in music history; her visibility and success is a matter of commodification, being in the right place at the right time, not some new, queer revolution. That being said, I find her videos HIGHLY relatable (the unrequited love parts because I am emotionally stunted), fun to watch, and I’m old so who am I to judge. I am not proposing that we disavow a successful young, queer woman; I am suggesting that it is possible to enjoy something and to be critical of it. That it is better to notice who rises to the surface during particular cultural moments, and to critique rather than pledge blind allegiance to any attractive woman who kisses girls and capitalizes on it. Let us ingest our pop stars and be forever critical of them, the industries that churn them out, and the gatekeepers who grant them access to audience.